The Freedom to Create

Picasso famously said, “All children are artists. The problem is to remain an artist once you grow up.” The first part of this statement is obvious to anyone who has spent time with children. They need no encouragement to draw and do so long before they learn to write. When no crayon and paper can be found, they locate a stone and scratch marks on the ground or make lines in the sand with a stick.

The second part of Picasso’s statement asks us to consider why adults are more hesitant to make art. The reasons are many, but the lack of artistic training is an important one. We tend to believe that artistic ability, especially when it comes to drawing, is a natural one; either you have it or you don’t. Yet no one one would expect a child to pick up a trumpet and figure out how to make beautiful music. Producing a convincing painting is no different: it requires disciplined learning.

Drawing can be taught

At RCA, we believe that artistic skills can be taught to all students. Within our curriculum, we emphasize drawing because it is the foundation for all other visual media, from painting to graphic design to architecture.

Most young children have only seen the symbolic, stick-figure type drawings that they and their friends create. But a more developed and representational style is possible, even at a young age. RCA has adopted the Monart Method, a drawing system that shows children how to perceive the visual world in terms of five basic shapes. With practice, they can identify them in any object and translate their perceptions onto paper. They are soon able to produce impressive drawings of anything they may observe, from insects to rocket ships to portraits of themselves.

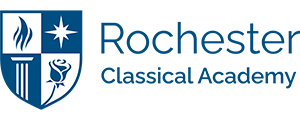

LEFT: The 7 year old student looked in the mirror as she drew herself. Without instruction in visual observation she could use only rudimentary symbols that were familiar to her.

RIGHT: After only one Monart lesson, she redrew herself with newfound realism.

Imitation as a gateway to creativity?

At RCA, students will draw from life and from their imaginations, but they will also copy from other well-established works of art. The idea of imitating another artist runs counter to the contemporary value placed on self-expression and originality. Why look to someone else’s style when we can discover our own? Doesn’t imitating stifle creativity?

Historically, part of any artistic training included copying from a master. The early Renaissance artist Cennino Cennini wrote The Craftsman’s Handbook, a how-to manual for aspiring painters. In it he admonishes apprentices to imitate the style of a master as closely and as often as possible. He says that if you copy from an excellent painter, “you will find, if nature has granted you any imagination at all, that you will eventually acquire a style individual to yourself, and it cannot help being good; because your hand and your mind, being always accustomed to gather flowers, would ill know how to pluck thorns.”

It would seem to be a paradox that it is through imitation, not in spite of it, we are able to develop our own style. Until relatively recently, nearly all artists – from Da Vinci to Velasquez to Sargent – imitated works of established masters as part of their training. Even artists who rejected traditional forms like Cezanne to Picasso were originally trained to draw representationally. Before he ventured into Cubism, Picasso could draw like Rembrandt. Michelangelo’s drawings after Giotto’s frescoes, whose style he so clearly departed from, reminds us that that imitation need not stifle creativity and innovation.

LEFT: Giotto, Ascension of John the Baptist (1315)

RIGHT: Michelangelo, after Giotto, (1490-92)

Learning to draw requires discipline that, for a time, will limit free expression. But once the skill of seeing and drawing is mastered, the artist has a powerful tool that allows her the freedom to create whatever she wishes! Someone who never takes the time to learn the skill in a disciplined manner has no such freedom.

Drawing across disciplines

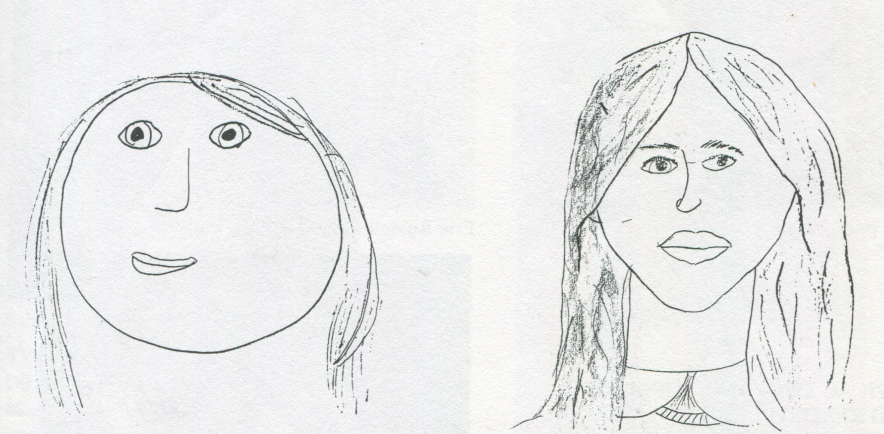

At RCA, drawing abilities can be enjoyed and utilized in many subjects outside of art. For example, students can use drawing to visually document the parts of a flower in a nature journal. With a more nuanced understanding of shape and proportion, students can produce a convincing map of the world with greater ease. It is difficult to forget what we draw because it requires us to slow down and consider all the details that are otherwise overlooked. If we want to learn all the parts of something, there is no better way than to draw it.

LEFT: Monart student, ship (age 6)

RIGHT: Monart student, drawing used in science lesson (age 11)

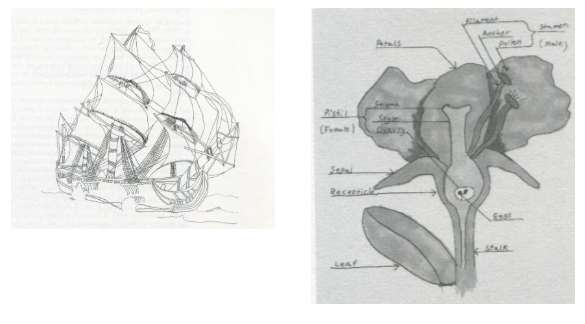

Drawing is an intellectual and joyful activity that allows us to discover the intricacies and beauty of the world around us. Our goal at RCA is not necessarily to create more professional artists, but to equip students to observe attentively, think aesthetically, and value beauty…far beyond childhood.

LEFT: Monart student, iguana (age 9)

RIGHT: Monart student, live bird study (age 11)

Want to talk more about art at RCA?

Send us an email to set up a time to talk on the phone or in person.

Ready to apply for admission?

Click here to read more about our admissions process and start your application.